By Stuart Hart, University of Vermont, Enterprise for a Sustainable World, Kate Napolitan, Enterprise for a Sustainable World, and Priya Dasgupta, Enterprise for a Sustainable World

When it comes to sustainability, the distance we’ve traveled over the past two decades will seem small when, in 20 years, we look back at the 2010s: We have succeeded in establishing pollution prevention and eco-efficiency as accepted ways of doing business; Our challenge now is to develop a truly sustainable global economy. This will mean trillions of dollars in products, services, and technologies that barely exist today. The question is: how many of today’s incumbent firms will have the vision, leadership and commitment to prosper from (rather than fall victim to) the greatest transformation in human history?

In recognition of this daunting challenge—and opportunity—for business, a research project was launched to benchmark the leading-edge “next” practices in companies aimed at driving such transformational sustainability. The project was designed to focus on the “outliers”—a sample of those few companies in the world pushing the envelope when it comes to Transformational Sustainability.[1]

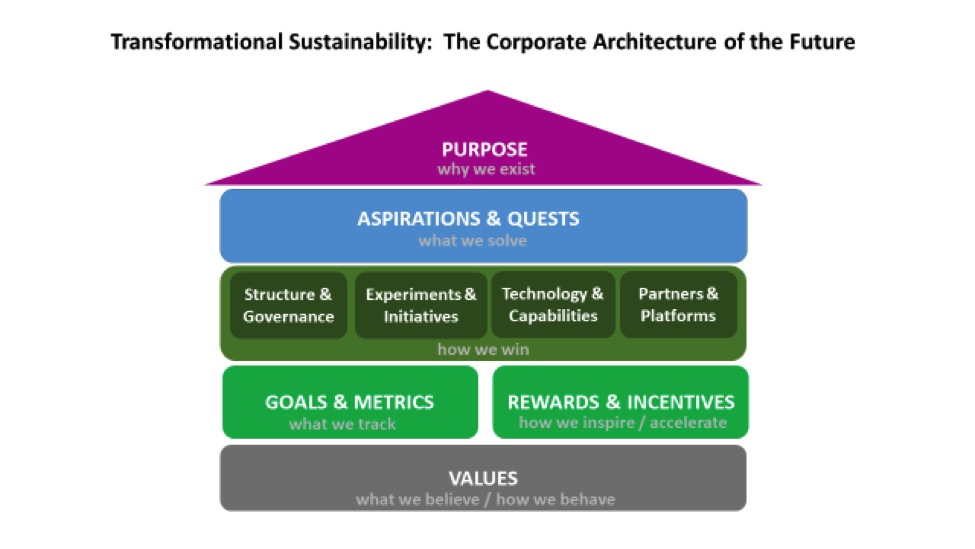

Our research reveals that confronting the challenge of global sustainability requires a complete rewiring of today’s corporations. Actually, it entails much more than just an upgrade to the electrical system: The corporate transformation to sustainability means nothing less than a rebuilding of the entire corporate edifice—a new “house.”[2] Indeed, there is an integrated set of building blocks and elements that appear to be essential if companies are to successfully chart the course for transformation. Taken together, these constitute a new architecture for corporate transformation (See Exhibit).

WHAT We Believe

The transformational companies we studied started with a strong foundation built on their organizations’ Values. These lived values, whether stated or unstated, make up the culture of the company and encompass what the company believes and how people behave toward each other and their stakeholders. A house with a poor foundation will not last – regardless of how large, visually appealing or expensive the house that is built on top of it. This foundation must be strong enough to support everything else the organization aspires to become. For example, SC Johnson has been guided by a strong set of principles since its founding in 1886. These principles were first summarized in a 1927 speech by H.F. Johnson, Jr: “The goodwill of the people is the only enduring thing in any business. It is the sole substance…the rest is shadow.” The values were more formally stated in 1976 in “This We Believe,” which sets forth five sets of stakeholders to whom the company holds itself responsible: Employees, Consumers and Users, General Public, Neighbors and Hosts, and the World Community.

WHY We Exist

The roof of the “house” consists of a clear articulation of corporate Purpose. Unlike past efforts to articulate corporate vision and mission, which were often competitive or technical in nature, transformational purpose gives voice to why the company exists—what positive impacts it seeks to have in the world. It is a moral call to action that fosters connection and commitment on the part of organizational members. The Unilever Purpose, for example, is “to make sustainable living commonplace.”

WHAT We Solve

Lofty statements of purpose can breed frustration and cynicism if they are seen as mere platitudes or fail to effectively connect to the real-world reality of managers and employees. To overcome this potential for disconnect, the companies in our study developed Aspirations and Quests to bring corporate purpose to life and serve as the “connective tissue” for goals and metrics, as well as rewards and incentives.

Focusing attention on a truly pressing challenge facing the world, for example, Interface declared that their next mission would be “Climate Take Back.” Their quest is to build a business that is carbon negative—and to influence other companies and employees to take their own actions to reverse global warming. The company has identified four pillars (Aspirations and Quests) to make this mission more tangible, with specific goals and metrics for each:

- Live Zero (aim for zero negative impact on the environment);

- Love Carbon (stop seeing carbon as the enemy and start using it as a resource);

- Let Nature Cool (support our biosphere’s ability to regulate the climate); and

- Lead the Industrial Re-Revolution (transform industry into a force for the future we want).

WHAT We Track and HOW We Accelerate

The transformational companies we studied have developed an interconnected system starting with Purpose which cascades to Aspirations and Quests, which in turn are operationalized through specific and measureable Goals and Metrics, and then reinforced through the Reward and Incentive system. Purpose is forever; Aspirations and Quests are enduring and serve as beacons for the development of strategy and business plans, but can also evolve as necessary; Goals and Metrics are expected to be updated, revised and amended periodically as the world (and business conditions) change; and Reward and Incentives are updated every year.

At Seventh Generation, for example, they focus on four Aspirations: Nurturing Nature, Enhancing Health, Building Communities, and Transforming Commerce. For each of these four aspirations there are associated long term sub-goals and each sub-goal has an annual short-term target.

HOW We Win

In order to live the Purpose and realize the audacious Aspirations & Quests, strategy and execution are key. [3] It takes organizational focus (Structure and Governance), iteration and adaptation (Experiments and Initiatives), investment in core competencies and innovations for the future (Technologies and Capabilities); and reaching out to the broader ecosystem (Partners and Platforms) to bring sustainable innovation to market at scale.

A Structure and Governance system with sustainability embedded within (as opposed to hanging off the side) establishes clear roles and responsibilities to enable the setting of priorities, decision-making and execution of strategy. This helps to guide the sustainability efforts starting with the Board and CEO and supported by a dedicated staff. At Unilever, for example, every Board Committee has a Sustainable Living Plan (Corporate Purpose) mandate to fulfill with the CEO held responsible for delivering results.

Such organizational clarity then enables the pursuit of Experiments and Initiatives—be they pilot projects or small market probes, new products and services, or a re-haul of existing business models—in line with the company purpose and aspirations. For example, Essilor has created a completely new Mission Division focused on bringing vision correction to the world’s underserved. This has catalyzed the development and launch of dozens of new technologies and business models aimed at reaching those 2.5 billion people in the world with uncorrected poor vision.

Ingersoll Rand provides a clear illustration of how the above two elements of company strategy for transformation fit together: The company’s governance structure includes both internal and external Sustainability Advisory Councils, along with the Center for Energy Efficiency and Sustainability. Ingersoll Rand is also one of the first industrial companies to have a CEO-level sustainability target focused on GHG reduction. This CEO target serves to frame the climate targets for the entire senior team, which then trickle down to all levels across the company, effectively making it a company-wide KPI.

When it comes to Technology and Capabilities, it is all about identifying and investing in the new, sustainable core competencies and technologies the company will use to transform the business in line with its Purpose and Aspirations. It may also be necessary to shed legacy products and technologies that are not in line with the future aspirations. Indeed, our research shows that leading companies typically invest 5% – 15% of revenue in R&D in the quest to transform themselves into tomorrow’s sustainable enterprise. Over the past two decades, for example, DSM has transformed itself from a petrochemicals producer into a science-based company with a focus on nutrition and innovating for the bio-based, circular and low-carbon economy of tomorrow.

Our research also shows that leading-edge companies are realizing that it is not possible to drive the transformational change required purely through changes in competitive or corporate strategy. Indeed, Strategic Partnerships and Platforms appear increasingly to be key to delivering on a wider, societal value proposition through partnership ecosystems and engagement in broader collaborative platforms that address systemic changes beyond the requirements or capabilities of the firm itself; an approach Dow has deftly described as Blueprint strategy. For example, Mars recently established the Farmer Income Lab—a collaborative think-do-tank aimed at elevating small-holder farming communities as a whole, thereby ensuring sustainable supply chains for the company well into the future.

Novozymes illustrates well these two elements of transformational strategy. With more than 10% of sales dedicated to transformational R&D, the company has launched a stream of new “game changer” products in bio-energy and sustainable agriculture. Novozymes has also forged alliances and partnerships aimed at advancing its sustainability goals, working with large customers, NGOs, and other players to shift the policy dialogue in the world toward more sustainable solutions.

Reconstructing the House

The above constitute the elements and building blocks required for companies to transform themselves to ensure a sustainable future. The first step toward such radical reconstruction is to do a comprehensive house inspection to determine which elements are outdated, missing or most in need of replacement. For most companies, this inspection will reveal that the best place to begin is by identifying the few Aspirations and Quests upon which to focus strategic and organizational attention. Once there is clarity about these priorities, the company can then develop the specific Goals and Metrics against which progress can be measured. Next comes an articulation of the “How” elements described above—where to play and how to win—including what new technologies, capabilities, and partners will be needed. Finally, the company can devise the means to most effectively integrate these elements with Reward and Incentives and ensure the alignment needed with other key company management systems to accelerate the corporate transformation required.

For more information, contact Enterprise for a Sustainable World at: stuart.hart@e4sw.org

[1] For details, see Hart, S., Napolitan, K., and Dasgupta, P. (2018). Transformational Sustainability Benchmarking, final report. Available upon request. We thank University of Vermont and Griffith Foods for support of this study.

[2] Our thanks to Griffith Foods for the use of the metaphor of the “house” in describing this transformation.

[3] Our thinking on this element benefitted greatly from an article by Roger L. Martin: https://hbr.org/2010/05/the-five-questions-of-strategy

____________

STUART L. HART is the Steven Grossman Endowed Chair in Sustainable Business at the University of Vermont’s Grossman School of Business and Co-Founder of the School’s Sustainable Innovation MBA Program. Bloomberg Businessweek has described him as “one of the founding fathers of the ‘base of the pyramid’ economic theory.” He is also the S. C. Johnson Chair Emeritus in Sustainable Global Enterprise at Cornell University’s Johnson School of Management, Founder and President of Enterprise for a Sustainable World, Founder of the BoP Global Network, and a Net Impact Board Member. His over 100 articles and nine books have received more than 35,000 Google Scholar citations. His article “Beyond Greening: Strategies for a Sustainable World” won the McKinsey Award for Best Article in the Harvard Business Review for 1997 and helped launch the movement for corporate sustainability. Hart’s best-selling book, Capitalism at the Crossroads, is amongst Cambridge University’s top 50 books on sustainability of all-time.

Priya is the Director of Strategic Initiatives at Enterprise for a Sustainable World. Over the past decade her focus has been on building strategic partnerships to create sustainable business ecosystems, especially at the base of the pyramid. Priya joined ESW from the World Bank where she served as a private sector development specialist. Priya holds an undergraduate degree in Electronics and Telecommunications from University of Pune and an MBA from Cornell University’s Johnson Graduate School of Management.

Kate brings over 15 years of sustainable business experience. She is a seasoned marketing expert with a deep understanding of many marketing disciplines including strategic marketing, market research, communications, and new product innovation and is actively applying these skills in the BoP space. During her ten years at Eaton, a power management company, she worked to bring green technologies to the market. Prior to her time at Eaton, Kate worked with Rocky Mountain Institute’s energy consulting services group, Ford Motor Company’s CSR group, and Environmental Resources Group regulatory consulting group. Most recently she served as judge for the inaugural Roddenberry Prize which awarded $1 million to support innovative solutions that address humanity’s greatest challenges. Kate has a Bachelor’s Degree in Engineering, a Master of Business Administration degree, as well as a Master of Science Natural Resources degree from the University of Michigan.